For Al Russo, the crooner’s magic is part of his life

HERALD NEWS ARTICLE

Reporter Tim Norris

For Al Russo, the crooner’s magic is part of his life

The summer wind had blown on by when Al Russo found Sinatra, again, at the foot of his hospital bed.

He always loved Sinatra, the humility of the man, the hard work, the way he could shape a song, the honesty in performance, the more than 1,200 recorded songs, never mind all those stories about ego and tirades and celebrity escapades. The ’40s Sinatra, the ’50s Sinatra and, even more, the ’30s Sinatra, the kid growing up in Hoboken, and the ’20s Sinatra, the infant who almost died at birth, that’s the man Russo was thinking about just then.

Russo needed a little of Sinatra’s magic, that day in 1999. The date was May 14, a year to the day after Sinatra had died in Los Angeles, at age 82. In early May, doctors had taken a malignant tumor out of Al Russo’s pancreas, had snipped out his gall bladder and redirected his digestive tract. For all too many, cancer in the pancreas is a death sentence.

And there was Frank Sinatra, on the TV set in the room in Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in New York, with news outlets nationwide splashing tributes.

Here was Al Russo, the accountant in his late 40s, the family man, wonderful wife, two beautiful daughters, who started out in Paterson at age 6 imitating Al Jolson on TV. He had grown up singing in street-corner bands with his second cousin, Lou Pallo, and with Joey Colucci and Joe Zizzo (the big-time drummer) and Guy Ventura and so many other budding and later successful musicians. He had heard for years that he could sing, too, and he sang at birthdays and in church and at get-togethers and charity events.

On that day in May, he thought for the first time about singing Sinatra, in public, for money.

“Sinatra took my mind off everything,” he says. “My oldest daughter, Rachel, she’s a good singer. I had this thought that maybe I could sing something of Sinatra’s with her, maybe in a club somewhere.”

Many aspiring singers have that urge, Russo knows. Sinatra imitators, tribute artists, evokers, some very good, some not so, ply the various entertainment circuits, from show stage to back yard and rec room. Without encouragement, without reward, he says, they wither.

Here he is, then, on a recent November night eight years later, in Mina’s on the Mountain, an Italian family restaurant in West Paterson, listening to his partner Garry Colletti, a contractor and also (as it happens) a former mayor of West Paterson, and wanting to be up there with him.

Colletti, with an easy smile, settles behind their massive music console and its microphone. He looks immediately at Russo and calls out, “I see my friend Al back there. No, no, Al, don’t get up.” Russo answers back, “Hey, I thought you were still sitting down,” and Colletti laughs and launches into “Somewhere in Your Heart” in a well-rounded baritone.

Russo had stepped into Mina’s main dining room gingerly, in slight pain and feeling a little awkward in a long-sleeved green shirt and wash pants instead of the customary tuxedo. Surveying the crowd, he takes a seat at the rear. A half dozen people approach, greeting him, smiling and then looking concerned. One woman raises her eyebrows in question and trowels her hands downward, at the waist.

At age 56, Russo is just coming back from another surgery, a second hernia operation. He thinks maybe the hernias came from lifting his music equipment, the player and mixer, speakers, monitor, stands, out of a car’s trunk. The player-mixer alone weighs 70 pounds. He has switched to a back-loaded van, picked up more compact speakers. This coming Thursday, Nov. 29 at 7, he plans to join Colletti again at Mina’s, and then on Wednesday, Dec 12, Sinatra’s birthday, also at 7, at Colucci’s in Haledon.

For now, he can only sit and yearn.

“Here’s one by Sinatra,” Colletti says, opening into one of his partner’s favorites, “The Summer Wind.” By halfway into the first stanza, Russo is quietly singing along: “Like painted kites, those days and nights, went flyin’ by …”

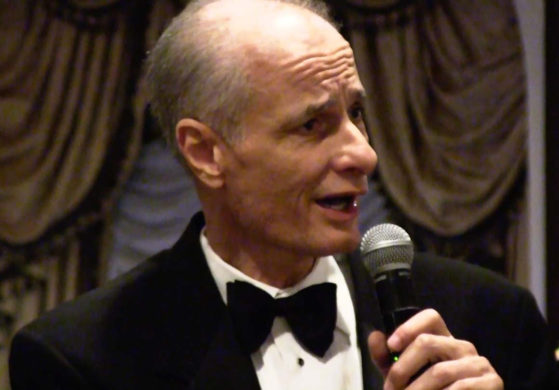

Russo is tall and spare, not pretending to be a Sinatra look-alike, or even an exact sound-alike, though there IS something of Sinatra in the angular jaw and shoulders and in the vocal lilt, too. Like Colletti, who favors Dean Martin and Engelbert Humperdinck, Russo does not imitate Sinatra but, he says, interprets his music, aided by the wonders of digital recording and portable karaoke-style sound and music-making equipment.

The contrast in stature between the two men echoes another two-man act with Paterson roots: Abbott and Costello. Colletti, shorter and rounder, has a mellow, elastic voice; Russo’s is smooth but edgier, more exacting. “Sinatra’s phrasing sounds so natural, but he was a precisionist as a singer, as an actor,” Russo says. “That’s the way I am, too.”

What led Russo to the professional stage was not Sinatra, he says, but another companion of his adult life: stress.

Think of tax time. The post-holiday tax rush is Russo’s bread-and-butter, and also his hammer-and-tong. He is not a number-cruncher, not a man driven batty by columns of figures. His accounting focuses, he says, on problem-solving, on life situations. People come to his second-floor walkup on Willow Way along the Passaic River with problems, with needs, and he gives them the best advice he can, working to save them money and deflect grief.

“Some of the tax laws are just crazy,” he says, “and owners of small businesses can really be hit. I get a lot of satisfaction out of helping them.”

Still, worrying through the latest changes in tax law alone might give a man the heebies and jeebies. And he had always been a guy who needed to be in control.

“I had the worries of any spouse or father, to provide,” Russo wrote, in a recent bio. “So work was all I knew. No hobbies. I made no time for anything else. I had forced vacations, not that I minded them, but being a one-man operation, I needed a month to catch up on a week’s vacation.”

Stress, in his case, had an unwelcome ally, a consequence of his depleted pancreas: diabetes.

When he learned he had developed the disease, in 2002, the treatment in St. Joseph’s Hospital in Wayne included a three-day course on easing its effects. Stress, he was told, aggravates diabetes. You need to do something to relieve it.

He had stepped in with his second cousin, Lou Pallo, in a club in New York to sing “My Way” and “New York, New York,” and the manager asked him to come back. Russo said he couldn’t do that without Pallo. The manager grinned and said, “Karaoke.” Russo had never heard of it.

So he bought a karaoke machine, discovered pre-recorded instrumental tracks, and monitors with lyrics, and Web sites such as Music Minus One and Pocket Songs for downloading music. He also picked up a definitive 50-song CD collection, “Simply Sinatra.” He took those and did what every good musician does, whether he or she can read music or, like Russo, can’t.

He practiced, every day and for several hours on weekends. And he sang where he could. People seemed to like it.

A friend, Craig Corvino, owned an Italian restaurant up on Browertown Road. When Corvino picked up an entertainment license in 2003, he asked Russo to take the first night. “Working live with that audience, feeling that reaction, made me want more,” Russo says.

Garry Colletti was singing there, too, on different nights. Colletti had grown up in what he calls “a four-room coldwater flat” in Passaic, and most of the family was musical. “Small as the house was, we’d have a band set up in the parlor,” he says. He went into masonry and contracting work but couldn’t forget the music. “Five or six years ago, my kids bought me a karaoke machine for Christmas,” he says, “and I haven’t stopped singing since.” The two men heard each other, sat in with each other, liked the mix and started teaming up.

They stepped into a kind of local live music circuit, into benefits and charity appearances and into gigs at restaurants and banquet halls such as Colucci’s in Haledon and the Brownstone in Paterson, Kopici’s in Bloomingdale and Bella Vita in Fair Lawn. To each, they bring a blend of tuneful, romantic music from the ’40s, ’50s and early ’60s, and they enjoy a good-humored banter between songs … and a little chance to rest while the other guy sings. They might make $150 each for a two-hour restaurant show, or $750 or more for a four-hour party or event. Mostly, though, the men say, they just like the energy, the live experience.

They share a common thrill, too. Colletti puts it this way: “I remember doing an Engelbert Humperdinck song, and people came up and said, ‘Were you lip-synching that song?’ That’s the biggest compliment.

“But it’s not just ego. Joey Zizzo and Friends, a great local group, they’ve been doing these afternoon events for senior citizens. I just did three of them at the Brownstone, singing to 300 to 400 seniors. They bring them in on buses, give them a luncheon, and have an hour-long Las Vegas-type show, and they asked if I would do some Dean Martin. That’s one of the most rewarding venues, to see the smile on those seniors’ faces, and Al and I will go up to the state or county nursing home, to Little Sisters of the Poor in Totowa or the Christian Health Center to play an hour or two, no money, and to the American Legion, the VA, the Elks, and that feels really good.

“Music gives a feeling. Maybe the word is ‘beauty,’ like looking at a great painting and feeling the excitement. When you sing, when you’re happy with what you’re doing, with the way the song sounds, that’s all that matters.”

Some of that feeling, Russo says, comes into the voice from life experience. Part of what people loved about Sinatra, he says, was that he had LIVED, had worked in clubs, in recording studios, in movies, had loved (those BEAUTIFUL women!) and fought and celebrated and suffered, right down to polyps on his vocal cords that, early on, threatened his career, that slightly dulled the clear bell tones in his voice and added a little gravel.

Russo thinks often, he says, of his wife, Robin, and his daughters, Rachel and Christine, and of that hospital room, with Sinatra. He thinks of how he lucky he was. His pancreatic cancer was self-contained, “like a pie,” he says, a rare event. “I didn’t need radiation,” he says. “I didn’t need chemo. They told me the tumor was so close to an artery that I could have had an aneurysm and died.”That night at Mina’s, he sits while Colletti sings, and with every Sinatra song he joins in. He plans, he says, to live a long time, singing Sinatra’s songs in his own way. More than anything, he says, Sinatra and his music endure. At least partly through that music, Al Russo does, too.